Japanese Embassy Hostage Crisis

The following article is a submission to the September 2011 J-Festa hosted by Japingu with the theme “Events in Japan”.

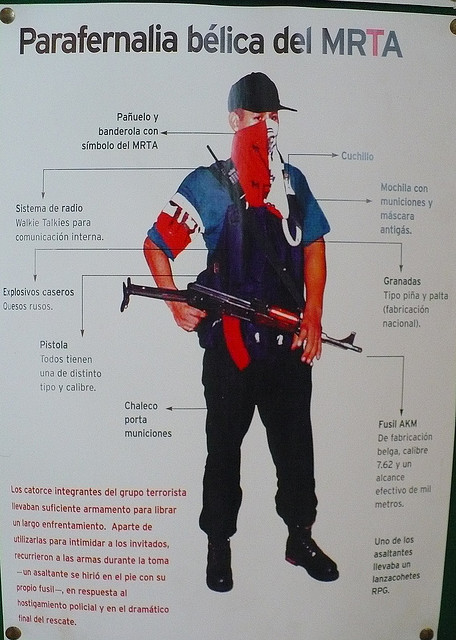

On December 17, 1996 the official residence of the Japanese ambassador, Morihisha Aoki, in Lima, Peru was raided by fourteen members of the Marxist revolutionary group Tùpac Amaru revolutionary Movement (MRTA). In what began as a festive occasion celebrating the 63rd birthday of Emperor Akihito soon turned into terror as hundreds of high-level diplomats, government and military officials and business executives were taken hostage (including 24 Japanese citizens). During the months that followed, the rebels released all female hostages and all but 72 of the men.

The crisis ended after 126 days in dramatic fashion as Peruvian Armed Forces commandos stormed the complex through underground tunnels, exploded holes in walls and direct assault through the main door, during which one hostage, two commandos, and all the MRTA militants died.

Ironically it may have been due to the diligence of the Japanese that saw a protracted hostage crisis. The Japanese ambassador’s residence had previously been converted into a fortress by the Japanese government. It was surrounded by a 12-foot wall, and had grates on all windows, bullet-proof glass in many windows, and doors built to withstand the impact of a grenade. This made it an easy site to defend from the inside.

Due to the high number of officials attending the cocktail party the complex had been guarded by over 300 heavily armed police officers and bodyguards. Nevertheless the 14 terrorists blasted a hole in the garden wall and stormed in. The rebels said they targeted the home of Aoki because of the “constant meddling of the Japanese government” in the South American nation. They singled out Japan’s foreign assistance program in Peru for criticism, arguing that this aid benefited only a narrow segment of society. Alberto Fujimori, Peru’s president at the time, is of Japanese descent and had close ties with Japan.

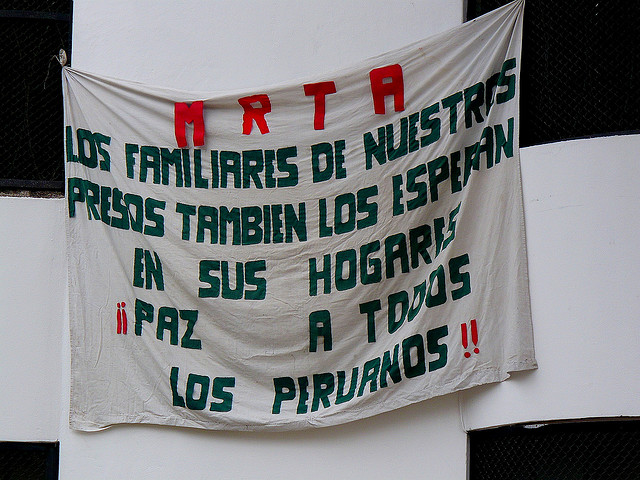

The MRTA insurgents made several demands, most importantly the release of about 400 of their comrades from prisons around Peru, including the leader, Nèstor Cerpa`s own wife. Publicly the Peruvian president, Fujimori, wanted a peaceful solution to the crisis. He created a negotiation team to find a peaceful solution, a team that included the country’s archbishop Juan Luis Cipriani, the Peruvian Red Cross, and the Canadian Ambassador Anthony Vincent, who had briefly been a hostage. He met the prime minister of Japan, Ryutaro Hashimoto in Canada and even talked with the Cuban leader Fidel castro, raising speculation that the MRTA guerrillas may be allowed to go to Cuba as political exiles. He also travelled to London to “find a country that would give asylum to the MRTA group”. Privately, however, Fujimori had no intention of allowing the rebels to succeed, or, arguably, even to live as upcoming events showed.

Fujimori´s private plan could be likened to something out of a Cold War spy movie. Over the course of weeks, cameras and microphones were being placed in key locations throughout the building by those hostages with military training, such as Navy Admiral Luis Giampietri. Brought in from the outside, these were hidden in water bottles, books and board games let in by the terrorists. The hostages themselves were allowed to have clean clothes, and the clothes sent in by the Peruvian Government were all light-coloured, which would later allow commandos to easily tell them apart from darkly clothed terrorists.

Extensive tunnels were being dug from adjacent buildings, leading to several key points under the Japanese residence. To conceal the noise patriotic music was played from the outside of the building while tanks repeated rolled back and forward. Terrorist leader Néstor Cerpa did, however, hear the sound of digging, and suspicious of a forced entry attempt moved all the hostages to the second floor, inadvertently helping keep them out of harm`s way.

And the rescue began on 22 April 1997, more than four months after the beginning of the siege. A team of 140 Peruvian commandos mounted a dramatic raid on the residence. Three explosive charges exploded almost simultaneously in three different rooms on the first floor. The first explosion occurred in the middle of the room where the soccer game was taking place, killing three of the terrorists immediately – two of the men involved in the game, and one of the women watching from the sidelines. Through the hole created by that blast and the other two explosions, 30 commandos stormed into the building, chasing the surviving MRTA members in order to stop them before they could reach the second floor.

Two other moves were made simultaneously with the explosions. In the first, 20 commandos launched a direct assault at the front door in order to join their comrades inside the waiting room, where the main staircase to the second floor was located. On their way in, they found the two other female MRTA militants guarding the front door. Behind the first wave of commandos storming the door came another group of soldiers carrying ladders, which they placed against the rear walls of the building.

In the final prong of the coordinated attack, another group of commandos emerged from two tunnels that had reached the backyard of the residence. These soldiers quickly scaled the ladders that had been placed for them. Their task was to blow out a grenade-proof door on the second floor, through which the hostages would be evacuated, and to make two openings in the roof so that they could kill the MRTA members upstairs before they had time to execute the hostages.

In the end, all 14 MRTA guerrillas, one hostage (Dr. Carlos Giusti Acuña, member of the Supreme Court who had pre-existing heart health problems) and two soldiers died in the assault.

According to the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), MRTA member Roli Rojas was discovered attempting to walk out of the residency mixed with the hostages. A commando spotted him, took him to the back of the house, and executed him with a burst that blew off Rojas’ head. The DIA cable says that the commando’s intent had been to shoot just a single round into Rojas’ head, and due to the mistake the commando had to partially hide Roja’s body under that of Nestor Cerpa. The cable also says that another female MRTA member was executed after the raid.

The rescue created much controversy which continues to this day. According to a Defense Intelligence Agency report, Fujimori personally ordered the commandos participating in the raid to “take no MRTA alive”. Peruvian TV also showed Fujimori striding among the dead guerrillas immediately after the raid; some of the bodies were mutilated. Fujimori was famously photographed standing over the bodies of Nestor Cerpa and Roli Rojas on the main staircase of the residence, and Rojas’ destroyed head is noticeable in the photograph. Shortly thereafter President Fujimori was seen riding through Lima in a bus carrying the freed hostages. The military victory was publicized as a political triumph and used to bolster his hard-line stance against armed insurgent groups. His popularity ratings quickly doubled to nearly 70 percent, and he was acclaimed a national hero. For everyday Peruvians the effectiveness of the rescue bolstered national sentiment. Antonio Cisneros, a leading poet, said it had given Peruvians “a little bit of dignity. Nobody expected this efficiency, this speed. In military terms it was a First World job, not Third World”.

Doubts about the official version of events arose soon after the rescue. Some aspects of what happened during the rescue operation remained secret until the fall of the Fujimori government. Evidence appeared to show that surrendered MRTA members had been executed extrajudicially:

-

One Japanese hostage, Hidetaka Ogura, former first secretary of the Japanese Embassy, who published a book in 2000 on the ordeal, stated that he saw one rebel, Eduardo Cruz (“Tito”), tied up in the garden shortly after the commandos stormed the building. Cruz was handed over alive to Colonel Jesùs Zamudio Aliaga, but along with the others he was later reported as having died during the assault.

-

Former agriculture minister Rodolfo Muñante, declared in an interview eight hours after being freed that he heard one rebel shout “I surrender” prior to taking off his grenade-laden vest and turning himself over. Later, however, Muñante denied having said this.

-

Another hostage, Máximo Rivera, then head of Peru’s anti-terrorism police, said recently he had heard similar accounts from other hostages after the raid.

Media reports also discussed a possible breach of international practices on taking of prisoners, committed on what was, under rules of diplomatic extraterritoriality, sovereign Japanese soil, and speculated that if charged, Fujimori could face prosecution in Japan.

What complicated matters further was that the bodies of the guerrillas were removed by military prosecutors; representatives from the Attorney General’s Office were not permitted entry. The corpses were not taken to the Institute of Forensic Medicine for autopsy as required by law. Rather, the bodies were taken to the morgue at the Police Hospital. It was there that the autopsies were performed. The autopsy reports were kept secret until 2001.

On 2 January 2001, the Peruvian human-rights organization APRODEH filed a criminal complaint on behalf of MRTA family members against Alberto Fujimori and some members of the Special Police and military. The bodies of the deceased MRTAs were exhumed and examined by forensic physicians and forensic anthropologists, experts from the Institute of Forensic Medicine, the Criminology Division of the National Police, and the Peruvian Forensic Anthropology Team, some of whom have served as experts for the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. Statements were taken from various officers who took part in the rescue operation and from some of the rescued hostages.

The examination done by the forensic anthropologists and forensic physicians revealed that Cruz Sánchez had been shot once in the back of the neck while in a defenseless posture vis-à-vis his assailant. Other forensic examinations established that it appears that eight of the guerrillas were shot in the back of the neck after capture or while defenseless because of injuries.

Domestic and international efforts to have the matter brought before the courts were eventually thwarted. Despite ongoing questions about the rescue, the commandos were honored and decorated, including those whom the judicial branch had under investigation for alleged involvement in the extrajudicial executions. On 29 July 2001, the commando squad was selected to lead the Independence Day military parade. This appeared to have been done to exert more pressure on the Supreme Court justices who had to decide the jurisdiction question raised by the military court, in order to make certain that it would be the military court that investigated the extrajudicial executions. The Supreme Court subsequently ruled that the military court system had jurisdiction over the 19 officers, thus declining jurisdiction in favour of the military tribunal. It held that the events had occurred in a district that at the time was under a state of emergency, and was part of a military operation conducted on orders from above. It further held that any crimes that the 19 officers may have committed were the jurisdiction of the military courts. It also ruled that the civilian criminal courts should retain jurisdiction over anyone other than the commandos who may have violated civilian laws.

Roughly ten months after the crisis began, Japan demolished its bombed-out and gutted diplomatic residence located in Lima’s residential area of San Isidro. “We are erasing the last remains of this nightmare,” a special policeman on guard outside the residence said at the time. “It’s a little bit more relaxed after all that tension”. The colonnaded home, built as a mockup of the antebellum home in “Gone with the Wind”, had been a shell since. The mansion’s walls were pockmarked with bullets and damaged by the bombs that exploded from tunnels underneath, while its crater-laden interior was blackened by fire.

In March 2006, a Peruvian court sentenced the leader of the MRTA to 32 years in prison. Victor Polay Campos was found guilty of nearly 30 crimes committed in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Other four high-ranking rebels also received long prison sentences. Polay and his fellow commanders, who were charged with crimes ranging from kidnappings to an attack on the US embassy compound, had been imprisoned at a naval base in Callao near Lima since 1992. They were sentenced to life in prison by a military court in the 1990s. But in 2003, Peru’s constitutional tribunal ruled that their conviction was unconstitutional and ordered a retrial at a civilian court.

This article was also featured in the February 2011 Japan Blog Matsuri hosted by reesan with the theme “Famous Japanese Events”.

Este es un claro ejemplo de una etapa de la historia peruana en la que los derechos humanos fueron atropellados al maximo en nombre de la lucha en contra del terrorismo por un ex presidente que el dia de hoy esta enjuiciado y preso asi como las personas que un dia victoriosamente salio a las calles a proclamar su captura.. esto nos demuestra lo injusto que fue nuestro pais con quienes lucharon tal vez sin saverlo por derechos que consideraban justos deacuerdo a su punto de vista a un punto de vista el cual no se conocia nadie sabia la realidad de los poblados alejados de Lima que no tenian comida,trabajo o derechos civiles como de los que gozabamos los que tuvimos la suerte de vivir en la capital en aquellosa anos… desconocimos de la realidad de nuestro pais por muchos anos y tuvimos que pasar por situaciones extremas en lima para llegar a la conclusion que habian otros hombres y mujeres viviendo en condiciones infrahumanas y desesperados por ser considerados e incluidos dentro de la sociedad con igualdad.

Fujimori was effective, I guess, but like all other effective leaders, that comes with an iron fist.

This didn’t get much press I think, but the siege itself was similar to what Mishima did in Tokyo. Interesting read. Thanks for participating in the blog matsuri.

Wow, what an interesting piece of history. I can see that it would be a bit controversial, though, as you mention.

Wow indeed- that was a really good (researched) post. Loved it… as much as such a grisly tale can be liked.

Cheers!

Once it said Marxist Revolutionary Group for describing the MRTA I stopped reading the article…it should’ve start with …the Terrorist Group…then I would’ve continue.

The action (the hostage taking) was the last of this Terrorist Group.

I was there. Along with 7 other Americans, I was taken hostage by the MRTA along with the other guests at Ambassador Aoki’s residence on December 17, 1996. All of the Americans were released 5 days later. Ambassador Aoki was a true hero as was Foreign Minister Tudela. They argued with the MRTA for humane treatment of the hostages. I will never forget the two of them on the staircase the night of December 22nd when most of the hostages were released — just before we left, Foreign Minister Tudela looked at us and said, “Feliz Navidad!” — Merry Christmas.

I also remember the first night when “El Arabe” — Rolli Rojas stood on the same staircase and began reading out names from the invitation list in order to separate the hostages. I was called upstairs and began five days in Room F with other diplomats. The room had been the Aoki’s breakfast room and I found a spot under a table in the corner and lay there on the floor.

It happened the same day I landed in Lima. I was picked up by family member and on purpose driven as close as possible to the embassy surrounded by soldiers and tanks. That place was on our way home. Next months went on reading the daily news. Public was rather disappointed in , what happened to look like complete lack of action. We did not know that during that time a perfect copy of the buildings was erected in the military base and special commando was training daily (often in total darkness) so at the end they new every inch of those buildings. I think it was an unprecedented action. Those that are upset by the fact that all the terrorists were killed, probably would think differently if they were among the hostages.